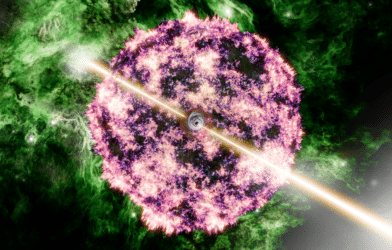

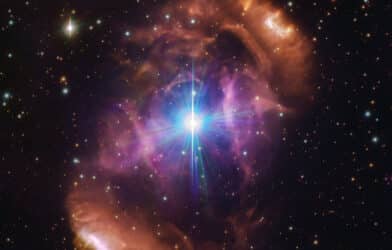

Stars live fascinating lives that end in even more fascinating deaths. Massive stars go out with a bang, exploding as dazzling supernovas that outshine entire galaxies. But even after these detonations fade, the cosmic story sometimes takes an unexpected plot twist as a team of astronomers found a stellar explosion that just refused to go quietly into the night.

Not only was the blast, dubbed AT2022tsd or “the Tasmanian devil,” brighter than a typical supernova, it also kept flaring back to life months after it was supposed to be dead and gone.

“No one really knew what to say,” says study lead author Anna Y. Q. Ho, assistant professor of astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences at Cornell University, in a media release. “We had never seen anything like that before — something so fast, and the brightness as strong as the original explosion months later — in any supernova or FBOT. We’d never seen that, period, in astronomy.”

Fast blue optical transients (FBOTs), first discovered only in 2018, are a bit of an oddball. They shine far brighter than regular supernovas, but fade away in mere days instead of lingering for weeks. Astronomers have puzzled over what could drive such extreme yet short-lived outbursts.

The “Tasmanian devil” FBOT, spotted about a billion light years from Earth, started off looking pretty typical. But when the astronomers checked in on it three months later, expecting it to have faded away, they saw something astonishing.

“Amazingly, instead of fading steadily as one would expect, the source briefly brightened again — and again, and again,” explains Ho. “LFBOTs (luminous fast blue optical transients) are already a kind of weird, exotic event, so this was even weirder.”

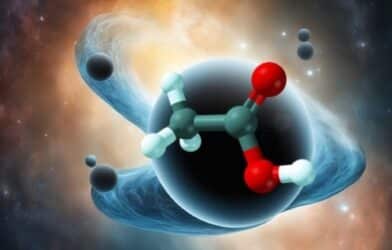

These enigmatic flares, picked up by 15 telescopes around the world, are something completely new to astronomy. The team believes they must be coming from the hyper-energetic corpse left behind by the explosion — either a black hole or a super-dense neutron star.

“We don’t think anything else can make these kinds of flares,” notes Ho. “This settles years of debate about what powers this type of explosion, and reveals an unusually direct method of studying the activity of stellar corpses.”

Exactly how the remnant is shooting out such powerful bursts remains a mystery. One possibility is that a newly-born black hole is flinging jets of stellar material outward at near-lightspeed. Or perhaps FBOTs aren’t regular supernovas at all, but are triggered when a star gets swallowed by a black hole.

“This is unprecedented behavior — most supernovae explode once and then steadily decline in brightness over the course of a few weeks until they disappear from view,” says study co-author Vik Dhilon, professor from the University of Sheffield’s Department of Physics and Astronomy who leads the ULTRACAM project.

Usually, astronomers only get snapshots of different stages in a star’s life and death — the living star, the explosion, the remnant. But with FBOTs and their lingering flares, astronomers might have a chance to watch a star’s full transition into its afterlife in real-time.

“Because the corpse is not just sitting there, it’s active and doing things that we can detect,” said Ho. “We think these flares could be coming from one of these newly formed corpses, which gives us a way to study their properties when they’ve just been formed.”

The find also hints that the way a star lives might foretell how it will die. Astronomers suspects that stars that spin very fast or have strong magnetic fields during their lives might be the ones that go out as FBOTs. Cracking that code could help astronomers link different kinds of stellar remnants to the stars that made them.

In the case of this undead star, one thing is clear: sometimes, the end is just the beginning of a whole new story waiting to be told.

Comments